Presentation Page 1

photo credit: Jason Pier

Thomas Jefferson, father of the U.S. patent system and an inventor himself, had this say about intellectual property.

"That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation."

Patents are about spreading ideas — that's why we have them. There are times when the best way to spread an idea is to grant exclusivity to its inventor in order to encourage investment and enterprise. But, ultimately, the goal is to get ideas out there — to encourage more acts of imagination and innovation.

I think we can do a better job of this. I think the world needs to do a better job of this.

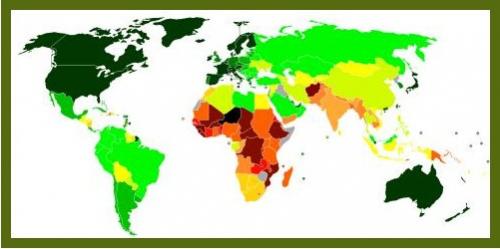

Here's what I mean. This is an intellectual property map.

The areas in green are countries with a lot of patents and a lot of money. Dark green also correlates with higher per capita income and less poverty.

The areas in orange and red are countries with fewer patents, countries where people are dying and poor. The darker the color, the higher the rate of premature death and the lower the per capita income.

There's clearly a relationship here.

As an intellectual property lawyer, I see ideas as key to economic development in the developing world. I know they say that when you have a hammer every problem looks like a nail — but in my case, I've run the numbers and they really are nails.

Let me tell you a story.

In Spring 2007, as I was obsessing about issues of intellectual property, I heard from Solomon Diamin*, a 30-year-old entrepreneur in Nigeria. Solomon needed to file a patent in the U.S. This wasn't a big deal — there are 1/2 million patents filed in the US every year, what's another one? And since I was the only patent attorney to respond to Solomon's email, he was more than happy to get on a plane and fly 22 hours to meet me in Raleigh, North Carolina.

After we figured out his patent matter, we chatted. Solomon's core business was cell phone tower management. Business was growing, but he had a big problem. His towers ran on diesel generators — and the diesel fuel he was paying for wasn't all getting delivered. So he was hiring a team to design a remote monitoring system for his tanks. This way, he could hold his delivery people accountable for filling his tanks.

And then, I had an epiphany.

But before I let you in on my epiphany, let me tell you some more about what it's like to deal with intellectual property in Nigeria and developing nations in Africa.

When companies apply for patent protection, they apply by country. If there's no market, they don't apply. As a result, Nigeria, Ghana, Zambia, Sierra Leone, and much of Sub-Saharan Africa is a dead zone when it comes to patents.

To me (and to Thomas Jefferson), this means the system is breaking down. The ideas aren't spreading. Why? Because people aren't seeing the full picture. They're looking at the "glass half protected," if you will.

Where there is no patent protection, there is no patent restriction. This creates the perfect condition for innovation. Because being unencumbered by patent restrictions means you can take advantage of patent applications — which collectively represent the largest how-to guide in the universe. Patent applications are by nature teaching documents. They must be written so someone of ordinary skill in that area could make use of the invention.

What do developing countries need? Intellectual property that solves problems. That lets them go from point A right to point W or X or Z. That's what the patent system can do. It can help the developing world develop.

And this would help the whole world.